Unsound Mind Introduction:

Personal introduction to the broadcast of Unsound Mind with BTS video of the North Pennine Moors

Unsound Mind

Final Realisation: Performance of Unsound Mind

“Nature bestows her gifts and makes no comment” (Schaeffer, P. 2012 p. 157)

Background:

The outcome of the experimentation of field sound recordings recorded as a series or blog posts is the creation of a complete and non-curated soundscape. It is the culmination of technical experimentation, narrative exploration and self-expression and was performed to a live audience, December 2025, at the University of Cumbria.

Unsound Mind is a sound composition of the polyphony of a North Pennine moor incorporating its biophony, geophony and anthropophony (Krause, 2015). Soundscape, a term coined by (Schafer, 1977), a composer and sonic artist, refers to the dynamic and ever evolving landscape of found sounds. Schafer exhorts artists using field recordings to:

“…to regard the soundscape of the world as a huge musical composition, unfolding around us ceaselessly. We are simultaneously its audience, its performers and its composers” (p. 205).

In the recording of the source material and subsequent performance I have been constantly reflecting on:

- How can sound lead the narrative of the film for my final project?

- If there is no script- what is the story?

- Is it realistic in an era of attention economy to expect people to engage with a non-curated soundscape?

- How will I test the audience response?

In resolving the final composition, I have been able to provide some answers:

- A soundscape is the narrative (see Blog Week 6 for a summary).

- The story is the experience of wildlife living on a North Pennine moorland habitat.

- Audience feedback from the performance provided good evidence that, given the right setting, introduction and composition there were no attention issues.

- See below for how the audience response was tested.

Phenomenology is defined by (Gallagher, 2012) as a means of describing the way we perceive things through our conscious experience which can differ from the materiality of the object. We should ask ourselves the question: what “precisely” do we see, hear, feel, perceive- set aside our prior knowledge which pre-shapes our perceptions- see anew, afresh- do we learn anything from doing this? (p.46). For me listening to the sounds of the birds on the moor was an emotional, intimate experience and I am now clearer in my narrative intention in both composition and performance: to communicate the essence of this self-reflection. Anderson, I. and Rennie, T. (2016) argue that field recordists, even if unintended, while recording for wildlife sound are creating a narrative. Even when they have a primary scientific purpose. They encourage field recordists to elevate themselves from the role of sound collectors to sonic artists: “…providing greater potential engagement for listeners” (p. 228).

My mid semester reflection (Blog Week 6) on encoding and decoding (Hall, S. 1973) was a turning point and provided the conceptual clarity I was seeking as a guide to the final composition.

Editing plan:

Selection and compilation of the source material collated over the previous weeks.

The sound files were labelled and backed up.

Narrative: the sequencing was the most difficult stage of the composition.

Considerations included:

- Temporal- creating a chronology

- Spatial- creating a literal flow from source of spring to full flow

- Sonic- aural transitions ie sound of water and wind

- Literal- grouse to beaters to shooting.

One of the key questions was where to insert the gun shots:

- At the end- for a dramatic conclusion to the piece

- If not where- how would this impact on the audience (see feedback)

I kept the editing process fluid to allow for changes in sequencing during the composition process and finally decided on the following (the red is how I anticipated the audience reaction to my encoding):

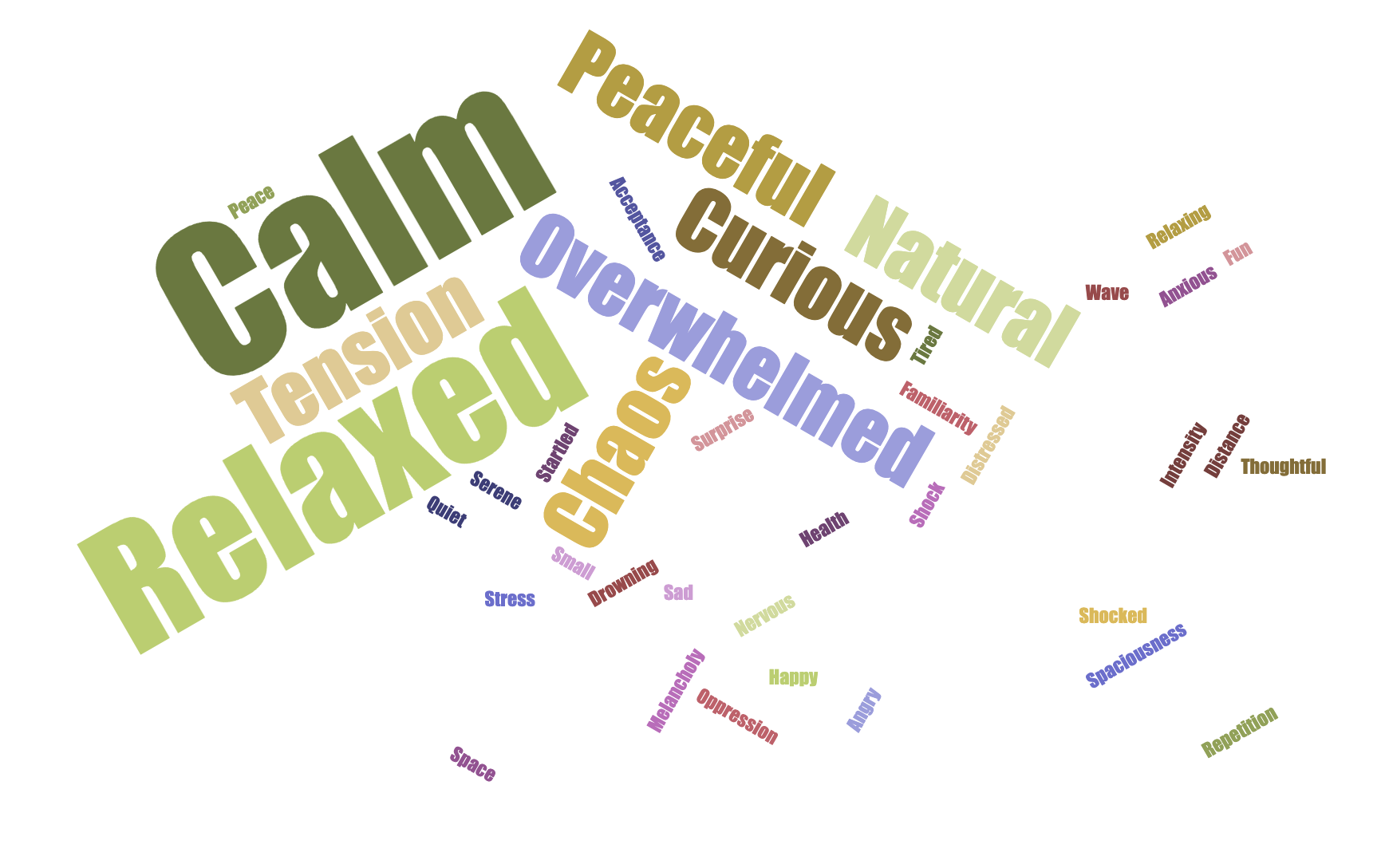

- Start on moor, 10 seconds of silence, then quiet ambience and lots of good bird sounds: grouse, fieldfare, owls, lapwing Peace, safe place, transported to an outside space.

- Aural transition to beater calls. Build volume. Build sense of place, maybe confusion of where the space first imagined is. Tweak curiosity- a narrative has started.

- Sudden loud crack of gun fire (delay second shot slightly) Shock, tension, attention

- Brief silence (complete?) Disquiet, uncertainty about what is coming next. Less safe than initially felt.

- Introduce rain and build to heavy downpour. Pathos for the shot birds. Immersive continues the sense of unease.

- Introduce water flow sequence- spring to cascade with lots of tonal layering. Going on an aural journey- the narrative has moved away from the wildlife to the landscape.

- Transition to wind sequence- lots of tonal layering and move to Aeolian sounds. Uncertainty about what the sounds are: intrigued. Introduces a feeling of enchantment

- Transition to buzzard calls, rooks, geese. Geese flying overhead. Return to a settled safe space again, curiosity- beginning to wonder how the piece might resolve.

- Aural transition to helicopter rotary blades and to Hartside traffic. Discomfort but also familiar- our human world- nature has gone- does that make people comfortable or uncomfortable?

- End with cyclist? Cheery “Good Afternoon” Conclusion with quiet- a former time of non-combustion engine transport, still able to hear the natural world and have time for a civil greeting. Feeling upbeat?

Editing a sound only composition provided freedom from the need to synchronise with a visual image. This creates more freedom for experimentation and adding sound effects in the mix ie stereo panning of the vehicles, aural transitions and aural pacing.

Broadcast Plan:

The best way to test the final piece was on a live audience. A few university staff and students were invited to a performance. Most were unaware of the content other than it was a short soundscape. The university’s main theatre was used as the venue. The in-situ sound system and theatre lighting were perfect for creating my preferred listening ambience.

Thinking again of wanting to share my personal recording experience with the audience I decided to recreate the feeling of pre-dawn isolation on a moor with the only illumination being dimmed blue filtered lights. The lights facing the audience helped to create a separation from the source of sound. The broadcast was played in stereo and the audience seated centrally to maximise the panning effects.

Preparation:

o Set up with technician support- sound and theatre lights

o Film and sound record- test mics- Lav mic on me.

o Feedback sheets and pens- questions:

What images are created?

What emotions are induced?

Any other thoughts, insights, advice?

Personal Introduction:

I decided to include a short, prepared introduction to set the scene- here is the script:

This broadcast is part of my MA studies and forms part of a journal of experimentation and exploration. My focus has been on field recording and, as part of that, I am keen to gather audience reaction.

As such, if you don’t mind, I am sound recording the event and making a timelapse video for my journal.

In 1952, in New York, the composer John Cage performed his famous, some say infamous, Silent Piece: for 4 minutes and 33 seconds the orchestra sat, in position but in complete silence. It has since become known as 4’33”.

John Cage’s intention was to comment on the ubiquitous streaming of background Muzak to which no one listens. He viewed this as a kind of mindless, passive, noise pollution and his Silent Piece was, in part, making a point about people losing the skill of listening.

As a conceit I have used John Cage’s timeframe of 4’33” and have filled it with found sounds from the North Pennine Moors.

Everything has been recorded, in situ, over the past ten weeks. In his diaries John Cage talks about being in the woods and conducting his Silent Piece to the mushrooms: he imagined the sound of insects crawling through their gills and the sound of their spores landing on the fallen leaves. These imagined sounds helped to inform his new compositions.

My recording is not that subtle! I have been experimenting with the discovery, recording and editing of found sound: biophonic, geophonic and antropophonic

and I have composed these, as a non-curated narrative- without the help of dialogue or music. Having now completed the edit is now titled: Unsound Mind.

In homage to John Cage the piece starts with a short silence. If you don’t mind I shall turn off the main lights and I should like you just to relax and, if you are comfortable, close your eyes and forget about the others around you. I have provided a feedback sheet for you to jot words or thoughts before you leave: please note down the images that come to mind and any feelings or emotions induced by the sounds. Try not to be distracted by trying to identify the sounds.

Audience Feedback

Word cloud of “emotions”

Written Observations:

- Feeling small and part of something bigger

- I like listening to language I can’t understand

- Feeling of transitory places- homesick maybe

- Overwhelmed with overlapping of sound

- Would like a longer silence at the end

- Drowning in the water

- The end made me wonder how man and nature work (or don’t work) together and the [spoken] “afternoon” made me think of working together to help nature

- Maybe a bit overwhelmed with the speed of different sounds coming “at me” but never getting “too close”- more like a wall of sound in front.

- I thought throughout it made you feel part of the landscape while at the same time only allowing you the opportunity to be a spectator without the ability to interact or change what was unfolding. For me personally my highlight was the running water which came to an 'almost' 4D experience. I put this down to the fact that I go open water and wild swimming so it was taking me back to those moments in time when the water was running over me. If someone had aimed some water spray at me I could easily have said I was there physically in the moment.

Audience Verbal Observations:

- Sounds are powerful emotional triggers: memories of flooding, feeling homesick, loved the intimacy the grouse (empathy increasing the reaction to the gun shots?), good transitions, wanted a longer silence at the end, weren’t impatient for it to finish

Reflections:

- Strong and diverse emotional responses

- No one commented they were bored!

- Some very strong reactions.

- People were transported to various locations: those unfamiliar with the actual place conjured up their own.

- Good that some people reflected on conservation issues: relationship between people and nature.

- The theatre set up worked well- the lighting was particularly important: created atmosphere also having the blue lights facing the audience helped to separate them from seeing the speakers creating a “wall of sound” and sense of the sounds coming “at me”. This is clearly important in creating an immersive environment and intimacy (separating the audience members from those around them).

Next Steps (for Semester 2).

Where do I want to go? Develop a coherent framework and explanation for my narrative style. In particular review and expand on concepts introduced during this semester: “gentle counter-narrative”, self-reflection, phenomenology etc. What is a non-curated style and what are the advantages: letting nature speak for itself without reliance on anthropological techniques or clichéd plots.

How do I use the learning from soundscape development and apply it to my final project film?

Do I instead or as well create a standalone sound installations?

Study more about link of sound and emotional memory

Recording and editing in immersive sound formats: object based like Dolby Atmos and channel based (5.1.2 or 7.1.2).

References:

Anderson, I. & Rennie, T. (2016). ‘Thoughts in the Field: 'Self-reflexive narrative' in field recording’. Organised Sound: an international journal of music and technology, 21(3), pp. 222-272.

Gallagher, S. (2012) Phenomenology, Palgrave Macmillan.

Hall, S. (1973) ‘Encoding and Decoding in the Television Discourse’, Paper for the Council of Europe Colloquy on “Training In The Critical Reading Televisual Language”. Organised by: Council and the Centre for Mass Communication Research, University of Leicester. Available at: https://www.scirp.org/reference/referencespapers?referenceid=3989724 (Accessed: 5 November 2025).

Krause, B. (2015) Voices of the Wild: Animal Songs, Human Din, and the Call to Save Natural Soundscapes. Yale University Press.

Schaeffer, P. (2012) In Search of a Concrete Music. Translated from the French by C. North and J. Dack. University of California Press.

Schafer, M. (1977) Our Sonic Environment and The Soundscape: the Tuning of the World. Destiny Books.